Cut. Rewrite. Cut Again

Oct 19, 2024

What Jane Austen, Tolkien, and a red pen can teach us about the writing process—and our children

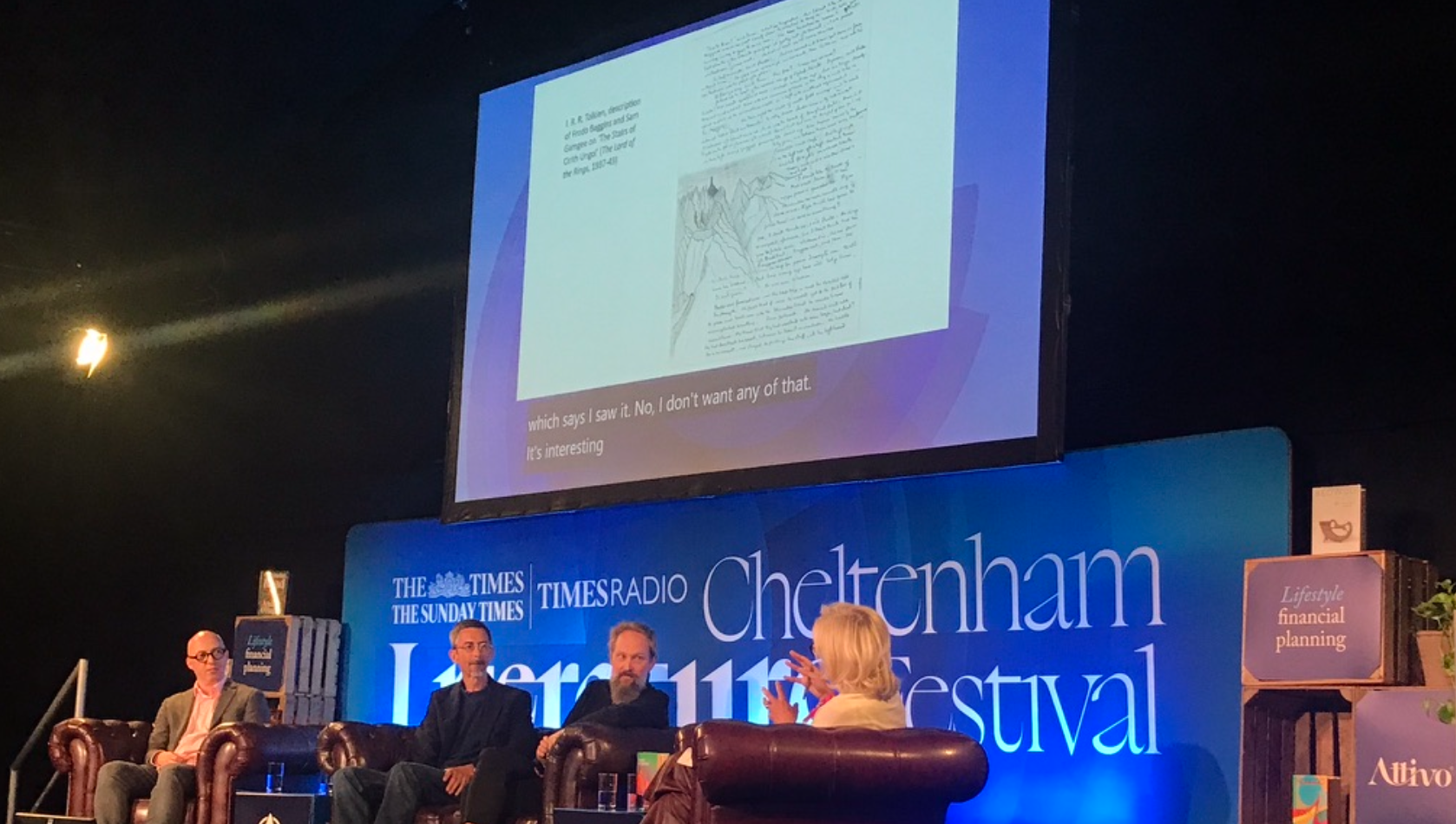

This year at the Cheltenham Literature Festival, I had the absolute joy of attending the “Cut. Rewrite. Cut” talk—a fascinating session led by the curators of the Bodleian Library’s exhibition exploring the first drafts and creative processes of some of the world’s most celebrated authors.

What unfolded in that room wasn’t just literary history—it was a reassuring, liberating insight into the messy, magical, and deeply human process of writing.

Even the Greats Needed a Bit of Help

We learned that Jane Austen couldn’t spell and heavily relied on her editor to correct her grammar. That Tolkien illustrated his stories as he wrote them, bringing mountains to life visually as much as textually. And that some poets and authors expressed their ideas through drawing before putting them into words.

As someone who now supports children in writing their own stories—this was a powerful reminder: writing is not a solo pursuit, and definitely not a perfect process.

Expression and Editing: Two Separate Superpowers

The most affirming takeaway for me was the recognition that storytelling and editing are two entirely different brain functions. To express a story is one thing; to shape, refine, and polish it is quite another.

It’s something I wish I had been taught at school. Perhaps I would have viewed that dreaded red pen not as criticism, but as a second stage of the creative journey.

And it got me thinking: how many children struggle with writing not because they lack ideas, but because they’re being asked to create and critique simultaneously?

What This Means for Parents and Teachers

For children—especially those using storytelling as a way to make sense of the world, process emotions, or shape their identity—this knowledge is gold. It validates the need to let the creative expression flow first, before we concern ourselves with spelling, structure, or punctuation.

Imagine what might change if more adults recognised this? If we taught kids that messy first drafts, scribbled drawings, and half-finished thoughts are not flaws, but foundations. That editing is a skill to be learned after the story is told, not during its creation.

A Collaborative Craft

Writing a book—or any piece of meaningful storytelling—is rarely a solo act. It’s collaborative. Editors, illustrators, mentors, parents, teachers... all play a role.

This talk confirmed something I’ve long believed and try to model in my own work with children: there is no one “right” way to tell a story, and we do our young storytellers a great service when we give them the space to explore, express, and be messy.

Because from that mess, magic happens.

So Thank You, Cheltenham

For reminding us that even the most beloved authors made mistakes. That writing is a journey, not a performance. And that our job, as adults, is not to fix the story too soon—but to help children feel safe enough to share it in the first place.

And maybe, just maybe, to give the red pen a bit of a rest—at least until the second draft.

Are you curious about how storytelling can support your child’s emotional growth, resilience, and creativity?

Let’s talk

Because every story starts with a spark—and every child deserves the freedom to let theirs shine.